Download a PDF of this thinkpiece

About the Commission

The Social Mobility Commission is an independent advisory non-departmental public body established under the Life Chances Act 2010 as modified by the Welfare Reform and Work Act 2016. It has a duty to assess progress in improving social mobility in the UK and to promote social mobility in England. The Commission board comprises:

Chair

- Alun Francis OBE, Principal and Chief Executive of Blackpool and The Fylde College

Deputy Chairs

- Resham Kotecha, Head of Policy at the Open Data Institute

- Rob Wilson, Chairman at WheelPower – British Wheelchair Sport

Commissioners

- Dr Raghib Ali, Senior Clinical Research Associate at the MRC Epidemiology Unit at the University of Cambridge

- Ryan Henson, Chief Executive Officer at the Coalition for Global Prosperity

- Parminder Kohli, Senior Vice President EMEA at Shell Lubricants

- Tina Stowell MBE, The Rt Hon Baroness Stowell of Beeston

This commentary was written by Dr Maria Koumenta, Queen Mary University London.

The author gratefully acknowledges the contributions from members of the SMC secretariat.

Foreword

This think piece is one of a series, which explores some overlooked topics in social mobility policy debates. Occupational regulation is a form of labour market regulation which determines who can provide a specific service or enter a given profession. And it may be a more important factor in shaping opportunity than has been acknowledged.

There are a range of policies aimed at improving social mobility, and a great deal of focus is currently given to achieving a wider mix of socio-economic backgrounds (SEB) in the professions. This work almost exclusively focuses on changing the socio-economic mix on elite pathways, by improving access to high-ranking universities and access to the professions for those from lower socio-economic backgrounds. One example of this approach is the promotion of contextualised admissions in terms of education and contextualised recruitment into specific occupations. However an overlooked topic is the role occupational regulation has on social mobility.

There is a pressing need to evaluate the impact of these approaches. It is important to point out that, in the case of contextualised admissions, unless there is an increasing supply of opportunities, this approach at best amounts to a “zero sum game.” They simply swap people from one socio-economic background for those from another. We have little evidence to support the wider social or economic benefit of this, nor do we have a clear view about who the “losers” are, or quite what their levels of privilege may be. This is why it is important to understand the link between occupational regulation and social mobility.

As a leader of a further education college, it often strikes me that the most valuable qualifications which we teach are those which have some kind of regulatory requirement attached to them. This is one of the reasons why those in construction, electrical and plumbing, for example, tend to earn more than other trades. And when we design higher education programmes, any requirements in terms of licences to practise appear to add value to the qualification.

Economists call this occupational regulation. Its purpose is to protect consumers, but as a consequence it also regulates the supply of opportunities in the labour market. It has enormous influence on the value of qualifications and on managing entry to various professional and technical occupations. Yet it hardly ever features in debates about social mobility. How does the system work? How prevalent is it? How does it influence the labour market? Does it create unnecessary obstacles? Is it possible to change it? What might the impact be?

Of course, in many cases some form of occupational regulation is required to protect the consumer. But such regulation can also act as an artificial barrier to entry, making it harder for people to get into the occupation. Those from lower socio-economic backgrounds may find this particularly hard, as getting regulated or licensed can involve time, money and access to networks which they may not have. Therefore, it’s important to consider when regulation is required and how it can be implemented to keep consumers safe without imposing barriers to entering the profession on those from lower socio-economic backgrounds.

The Social Mobility Commission is very pleased to have commissioned this think piece from Dr Maria Koumenta, an expert in occupational regulation and labour market analysis, to look into this issue.

The piece is designed as an introduction to the topic, drawing out some of the social mobility implications of current practices and how these might be changed. There are some fascinating insights into how the system works and how it affects progression into some occupations because of familial knowledge (and how the barriers drop for the second generation).

It also prompts interesting questions such as whether some pieces of regulation can be amended or removed to open up access to the profession without compromising the quality of service and safety of the consumer. These questions might be particularly important for professions which have problems with access to those from lower socio-economic backgrounds or where there is a lot of historical regulation.

We hope the piece provokes a wider debate about the type of labour market regulation which can best balance the need for consumer protection and making professions accessible to those from all socio-economic backgrounds. And we hope it helps to broaden policymakers’ minds, in terms of the range of tools available for ensuring opportunities are available to the widest variety of people in the widest variety of places.

Alun Francis

Chair, Social Mobility Commission

Executive summary

Occupational regulation refers to the rules which determine whether a person can do a specific job or provide a certain service. It involves the enactment of legal barriers for entry into occupations, usually relating to the attainment of minimum qualification standards.

Occupational regulation is common in the UK labour market, with about 22% of the workforce working in a licensed profession. Being in a licensed profession can have some benefits, such as ensuring high-quality products and services for the public, as well as higher earnings for practitioners. However, it may also come at the cost of social mobility. This is because the regulations imposed can act as a barrier to entry into occupations. Our research evidence shows that it is harder for people whose parents are not already working in a licensed profession to work in these occupations and that the chances of entering licensed occupations become even lower as (1) the criteria to become licensed become stricter and (2) for professional and managerial occupations.

| Key findings: having a parent in an occupation improves a person’s chances of getting into that same occupation. However, in the case of licensed professions, this advantage is twice as large, particularly for professional and managerial occupations.

Children whose parents work in routine and semi-routine occupations are 30% less likely to find themselves working in licensed occupations compared to children whose parents work in professional occupations. This suggests that occupational regulation lowers social mobility. |

Occupational licensing and social mobility

Education is often put forward as the key lever that prepares young people with the knowledge and skills they need to secure successful futures as workers in the labour market. However, a growing theme in academic literature has been the role that occupations play in transferring opportunities from one generation to the other. This is important because research highlights that British children’s educational attainment is overwhelmingly linked to parental occupation and qualifications. Research has also shown that 4 in 10 children were more likely to be employed in the same occupation and organisation as their parents or follow similar employment patterns, such as inheriting their parents’ business and going into self-employment. For example, studies in Canada, the US and EU nations show that approximately half of individuals in self-employment report that their parents were also self-employed. In this think piece, we explore the role which occupational regulation may have on social mobility.

We start by reviewing the types of occupational regulation and how regulation has changed over time. We then discuss the impact it has on the labour market and look at how regulation affects social mobility, particularly through family and social networks. We highlight the high financial cost associated with becoming a licensed professional and argue that this is likely to be a significant obstacle in entering licensed occupations for those from less privileged backgrounds. We conclude with thoughts on how occupational regulation policy could improve social mobility.

We find that occupational licensing may limit social mobility as it increases the advantage of having a parent who worked in the occupation that their child also wants to practice. This is because having a parent in an occupation makes it easier for children to get into that occupation relative to someone without a parent in that occupation. But, if the occupation is licensed, a child’s advantage is even greater.

Types of occupational regulation

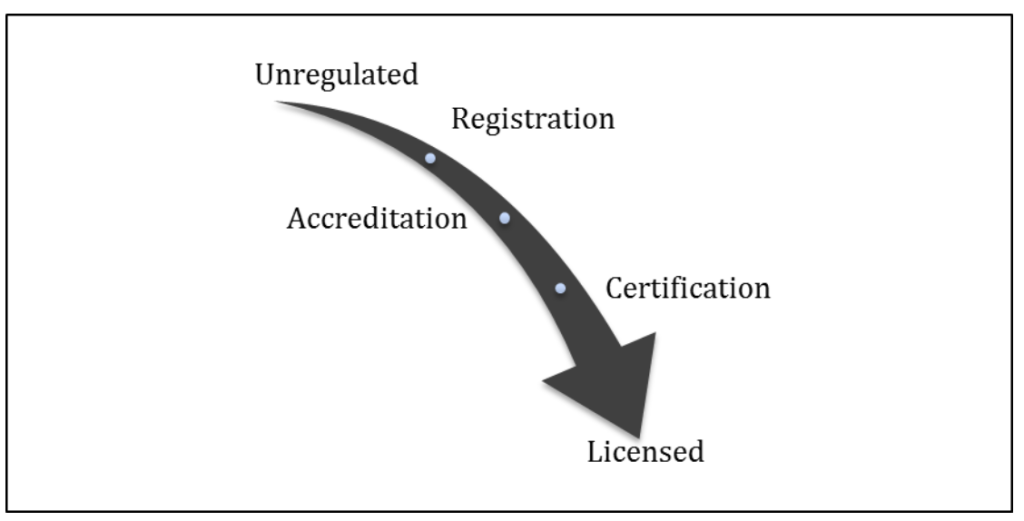

When considering occupational regulation, it is important to note that there are 4 different types:

- Licensing: refers to situations in which it is unlawful to carry out a specified range of activities for pay without first having obtained a licence. This licence confirms that the holder meets certain standards of competence. Examples of occupations that are licensed in the UK include doctors, nurses, solicitors, veterinarians, taxi drivers and driving instructors.

- Certification: refers to situations in which there are no restrictions on the right to practice an occupation. However, jobholders may voluntarily apply to be certified as competent by a state-appointed regulatory body. Examples of occupations that are usually certified in the UK include engineers, hairdressers, barbers and fitness instructors. Certification schemes are voluntary so a professional can still practice the occupation without being certified.

- Registration: refers to situations in which it is unlawful to practice without first registering your name and address with the appropriate regulatory body. Registration provides some form of legal barrier to entry, but an explicit skill standard is not a prerequisite to practice the occupation. Examples of occupations that can be subject to registration in the UK are estate agents, actuaries and investment advisors. For example, in the UK there is a requirement for estate agents to register with the Office of Fair Trading under regulations designed to prevent money laundering.

- Accreditation: refers to situations in which an individual may apply to be accredited as competent by an accreditation scheme provided by a professional body or industry association. This is opposed to being accredited by a state-regulated body, as is the case with certification where the state regulator decides which occupations are certified. Examples of occupations that are accredited in the UK are acupuncturists, dieticians, locksmiths and plumbers. Accreditation schemes are voluntary so anyone can practice the occupation without being accredited.

Occupations that do not fall in either of these categories are classed as unregulated. This means there are no restrictions to practising them.

The 4 types of regulation vary in how strict or lax they are in terms of acting as a barrier to occupational entry. Of the 4 types, registration is the most lenient type and licensing is the strictest. Figure 1 depicts the UK’s occupational regulation categories as a range from unregulated to licensed.

Figure 1: The occupational regulation range.

Source: ‘Occupational regulation in the UK and EU: prevalence and labour market impacts.’

The most common requirement to enter a licensed occupation is the requirement to complete some type of formal education. Depending on the skill requirements of the occupation, this involves obtaining a university degree or a diploma from an education provider recognised by the regulator or the professional body.

The attainment of educational credentials is in some cases followed by the requirement to sit examinations to be allowed to register with the relevant regulator and practice the occupation (known as the educational component of licensing). From the candidate’s perspective, this usually involves additional study time as the curriculum is tailored to the exam. In some occupations (for example, medicine or architecture) it is also common for the regulator to require individuals to complete a certain amount of work experience, which can range from 2 to 5 years (known as the vocational component of licensing).

These requirements pose some costs to individuals who wish to work in a licensed occupation. These include the cost of paying for the relevant basic and additional education, preparing for the examinations and paying the fees to register with the professional body or regulator. However, there are some indirect costs that we expect individuals to incur in the form of income loss associated with staying in education for longer than would have been the case without licensing as well as possibly having to accept lower income when the process to become licensed involves additional vocational experience that is not compensated. These costs can vary but we would expect them to be higher the more stringent the licensing regime relevant to the occupation. The overall effect is likely to create financial barriers to those from disadvantaged backgrounds as they are less likely to be able to afford the licensing training costs as well as the costs associated with staying out of the labour market while in training. From their parents’ perspective, it might not be possible to financially support their children during the training period, especially if this is entirely unpaid.

Who licenses occupations?

The introduction, oversight and administration of licensing in the UK is almost exclusively the responsibility of government agencies. Out of the 81 occupations that are licensed in the UK, 31 fall under the remit of a regulatory body (for example, the Health and Care Professions Council and the Civil Aviation Authority), 27 occupations are under the remit of a government agency (for example, the Driver and Vehicle Standards Agency and the Teaching Regulation Agency) and 15 occupations are under the remit of local authorities. Regulators’ statements in relation to the purposes and aims of licensing commonly include protecting the public interest as well as health and safety concerns. While some regulatory bodies consider issues of gender and ethnic representation within the occupation, whether and how their regulatory practices affect access to the occupation by individuals from lower socio-economic backgrounds is currently absent from their thinking.

Regulators are considered as unbiased and informed gatekeepers and enforcers of professional standards. In most cases, the members of these boards are practitioners or ex-practitioners of the occupation themselves. Their role is to screen entrants to the occupation and to exclude those whose abilities and skills do not meet the prescribed standards. They also monitor existing practitioners and discipline those whose performance is below standard with penalties or even the revocation of the licence needed to practice. Once an occupation is licensed, there is nothing preventing regulators from regularly introducing tougher entry restrictions and so increasing the cost of becoming licensed for prospective practitioners. Additional restrictions would include increasing the educational entry requirements, lowering the pass rate on licensing exams and lowering the number of available places in educational institutions. Regulations in the social care sector for example have been changed such that managers of residential and care homes were required by 2005 to have both National Vocational Qualifications 4 (NVQ4) in Care (or a Diploma in Social Work and also an NVQ4 in Management, not just the former as per the previous requirements.

Occupational licensing: evolution, rationale and characteristics

Occupational regulation is associated with the guilds, a deep-seated tradition in the UK’s pre-industrial cities. Such associations of skilled craftsmen were characterised by long, standardised periods of apprenticeships, exclusive rights to produce and trade in certain markets granted by the monarchy or local authorities, as well as tight control over materials and technical knowledge. As the UK economy became dominated by service sector occupations, the scope of occupational regulation increased. Shifts in the composition of jobs in the labour market (from manufacturing to service sector jobs) meant that a greater proportion of the population worked in occupations where the quality of the service that consumers would receive was more difficult to evaluate before the service was delivered and, in some cases, even afterwards. As a result, concerns regarding consumer protection surfaced and occupational regulation requirements were gradually extended to cover a larger number of occupations.

The protection of the public and health and safety concerns are the main reasons why the state regulates occupations. The assumption is that, due to a lack of expert knowledge and the intangible nature of services, customers cannot assess the quality of the product or service they receive, so occupational regulation provides these guarantees by standardising the skills of providers and protecting consumers from incompetent and unscrupulous practitioners. Through the provision of a common body of knowledge and skills within the occupation, consumers are likely to receive a more homogenous service than would exist without regulation. Educational requirements, entry tests and background checks ensure that prospective practitioners enter the occupation with common standards of competence. According to its proponents, licensing is also a means by which the state can intervene to increase the stock of skills among the workforce since it provides a legally enforced floor beyond which the skills within the occupation cannot fall. Finally, licensing is often put forward as a means to increase the professional prestige of occupations and solidify their legitimacy in the occupational hierarchy. In the early 1990s, osteopaths and chiropractors were successful in convincing the state to license their occupation to align their professions with the status enjoyed by conventional medicine. Similar arguments have been by the Care Quality Commission as part of a recent consultation into the prospect of introducing licensing for social care workers. Licensing, it was argued, would act as an indicator of professionalism, increase attraction to the profession and help address staff shortages in the sector. In other cases, we have seen turf wars within occupations in their effort to keep the occupation shielded from new entrants. For example, black cab drivers’ intense lobbying and jurisdictional claims over the topographical knowledge associated with their licensing status have ensured their monopoly of ‘ply for hire’ over ‘private hire’ taxis such as online taxi platforms.

Evidence suggests that occupational regulation is becoming more common. The latest estimates using the UK’s Labour Force Survey (LFS), shows almost a third of occupations (29%) are subject to licensing, affecting around 22% of the UK workforce (approximately 8.1 million workers). A study that also uses the UK’s LFS finds that the proportion of the workforce in licensed occupations increased between 1986 and 2012 from approximately 8% to 17%. Crucially, most of this growth was a result of more occupations being licensed rather than more people working in occupations which were previously licensed. However, due to the shifts in individuals working in manufacturing jobs (which are less likely to be licensed) to individuals working in service sector jobs (which are more likely to be licensed), we would expect some of the growth in licensed workers before the 1980s to be associated with more individuals being employed in these new jobs in the economy.

Table 1 presents a breakdown of the year that occupational licensing was introduced to various occupations in the UK. Occupations licensed before 1950 (21 in total) and occupations whose date of commencement is not known due to relevant historical records missing (a total of 13) have been licensed for a considerable amount of time and are commonly the professions in medicine, pharmacy, dentistry, law and accountancy. Since the 1990s, licensing was introduced for a total of 30 occupations such as psychologists, architects and several occupations aligned to medicine such as physiotherapists, medical radiographers and chiropodists. Reflecting on the evolution of licensing, it is evident that while for many decades the barriers to entering occupations were mainly confined to the traditional ‘professions’, recently we have seen the increase of licensing to what are known as ‘intermediate’ (also known as associate professional and technical) occupations. The implication of these developments is that the effect of licensing on social mobility is likely to be present not only at the top but also in the middle of the occupational hierarchy.

Table 1: Occupational licensing, by year of commencement.

| Regulation status | Before 1950 | 1950-

1979 |

1980-

1989 |

1990-

1999 |

2000-

2010 |

Don’t know | Total |

| Number | No. | No. | No. | No. | No. | No. | |

| Licensing | 21 | 14 | 3 | 15 | 15 | 13 | 81 |

Base: Standard Occupational Classification (2000) unit groups, map of occupational regulation.

Source: ‘A review of occupational regulation and its impact’, UK Commission for Employment and Skills.

Table 2 presents a breakdown of the number of licensed occupations by the major occupational groupings commonly used in UK Labour Force Surveys. Licensing is significantly more common among managerial and professional occupations such as medical and dental practitioners, opticians, veterinarians, solicitors, judges, coroners and various occupations allied to medicine. Examples of occupations which are licensed from the ‘skilled trades’, ‘personal services’ and the ‘operatives’ group include dental nurses, motor mechanics and auto engineers, driving instructors, some taxi drivers, heavy goods vehicle drivers and security guards.

Table 2: Licensed occupations by major occupational group.

| Licensing | Number of occupations |

| 1: Managers and senior officials | 11 |

| 2. Professionals | 15 |

| 3. Associate professionals and technical | 27 |

| 4. Administrative and secretarial | 0 |

| 5. Skilled trades | 8 |

| 6. Personal service | 6 |

| 7. Sales and customer service | 0 |

| 8. Process, plant and machine operatives | 10 |

| 9. Elementary | 4 |

| Total | 81 |

Source: Map of occupational regulation.

Finally, with respect to individual characteristics such as gender and ethnicity, we find that men are more likely to be licensed than women (table 3) and that White people are considerably more likely to be licensed than those from any other ethnic background (table 4).

Table 3: Gender of jobholder, by licensing status.

| Male | Female | |

| Licensing | 52% | 48% |

Table 4: Ethnic group of jobholder, by licensing status.

| White | Mixed | Asian or Asian British | Black or Black British | Chinese | Other | |

| Licensing | 88% | 1% | 6% | 3% | 0% | 2% |

How does occupational licensing impact the labour market?

The introduction of licensing means the demand for a universal and statutorily-based entry requirement to practice an occupation. As a result, we would expect the supply of practitioners in the occupation to fall, as low-quality individuals who cannot meet the minimum entry standard are barred from practising the occupation. The size of this reduction will largely depend upon the height of the new entry barrier to the occupation (the higher the hurdles, the lower the number of those in the occupation will be).

There is also a clear incentive to keep the hurdles high as the reduction in labour supply to the occupation may lead to an increase in wages in the licensed occupation. This means that the licensed practitioners will benefit from higher wages than if their occupation was not licensed. Extensive research in the UK, US and EU has consistently confirmed that licensed individuals earn considerably more than their unregulated counterparts in the labour market. A further potential drawback of licensing is that it could increase structural unemployment as entry to licensed occupations for someone wishing to remain in the labour market is delayed by the often lengthy and costly requirement to attain the necessary skill standards. Licensing can delay adjustments in the labour market. Finally, the impact of licensing can extend beyond the occupations in question. The inability to meet the required skills standards is likely to push prospective practitioners to unregulated neighbouring occupations. Such migration can lead to an excess supply of workers and a reduction in earnings in these occupations.

International perspectives on occupational licensing

From an international perspective, there are considerable variations in the professional regulation regimes across different EU Member States and the US. We note 2 main sources of variation. First in relation to the incidence (which occupations are licensed), and second to the nature of the licensing regime (how are occupations licensed). In particular, while some occupations are licensed in some Member States, in others they are unregulated. For instance, architects are not licensed in Denmark, Estonia and Finland, they are subject to certification in the Netherlands, but they are licensed in all other EU Member States including the UK. Norway only certifies dispensing opticians, in the rest of the EU they are licensed, while in the case of ophthalmic opticians, the Netherlands and Sweden certify the occupation while the rest of the EU licenses it. Where such regulations do exist, there are also differences in the entry restrictions that apply. These differences raise questions about the efficiency of licensing regimes and the scope for reforming regulatory requirements.

Germany and Italy have 2 of the strictest occupational regulation regimes in Europe, especially in the case of professional and highly skilled occupations with Belgium being on the other extreme and the UK and Ireland somewhere in the middle. Until recently, many occupations in Greece, Spain, Portugal and Poland were also heavily regulated, but following some reforms, there has been some relaxation of the entry criteria to certain occupations. Despite the reforms in some countries, it remains the case that throughout Europe professional and highly skilled occupations retain high barriers to entry and are represented by powerful professional associations who resist change and intensively lobby against it. The US has one of the strictest licensing regimes internationally, with considerable restrictions to entry in high-skilled fields like law and medicine, but also licensing requirements for even medium and low-skilled occupations such as interior designers, barbers and hairdressers. According to the latest estimates, a total of 22% of the EU and 20% of US workers are licensed.

The resistance to change by professional associations is evident in reform initiatives. When the Irish government for example was asked by the Troika to adopt legislative changes to remove entry restrictions in the legal profession, intense resistance by the Irish Bar Association meant that the final Bill enacted in 2015 was heavily amended so that it allowed legal professions to retain much of their original rights. Despite the Troika’s criticism, the legal profession representatives were powerful enough to resist the pressures to relax the regulations affecting the profession. Greece had a similar experience in the case of relaxing the entry regulations for the engineering and legal professions. Professional associations have traditionally enjoyed privileged access to Members of Parliament and close political connections with main parties which have compromised reform initiatives.

How does occupational licensing affect social mobility?

Our starting point is the literature that documents the transmission of knowledge and skills between parents and their children that takes place within the family unit. Within this strand of work, the focus is on how parents pass down important skills and competencies to their children related to their own education and competencies: a process that starts in childhood and continues as the child approaches adulthood. At this later stage, children are even more likely to receive occupation-specific knowledge from their family.

These are relatively low-cost transfers (in other words, there is not a large amount of investment by the parents other than using their time to share their expertise and experience) of relevant skills and insider knowledge that can not only play a role in affecting the child’s decision to join the occupation, but also provide the child with a relative advantage compared to others who have not been exposed to a similar context.

Research has shown that in the context of family law practice this transmitted knowledge is a significant factor in a son’s decision to follow his father’s legal profession and that second-generation lawyers who receive such help from their family have higher earnings than lawyers who have not had similar opportunities.

Another strand of the literature has documented the importance of social networks in the labour market. Such networks provide individuals with occupation and job-specific information, and this effect is stronger if the network comprises family members, relatives or acquaintances. This can be a two-way process. From the jobseeker’s perspective, the family and its networks can provide information about job vacancies and help establish personal connections with those currently working in the occupation, while from the perspective of the employer, it can provide information on the quality of the candidate which is otherwise difficult to determine before employing them. The value of social networks and occupation-specific family connections are likely to be higher in jobs where it is difficult to evaluate the quality of the candidate in advance, in other words, where trust is valued and reputation is an important signal of quality. Examples of these types of occupations are doctors, lawyers and accountants, and these happen to be the types of occupations that the state regulates.

The role of family and social networks on regulated professions

There are various reasons why we might expect a higher tendency to follow a parent’s occupation when the occupation is regulated, such as with licensing. First, entering a licensed occupation is associated with possessing occupation-specific knowledge and skills, such as meeting the licensing entry standards. Due to the specialised knowledge requirements to enter licensed occupations (a justification for imposing licensing restrictions in the first place), we would expect this knowledge and skills to be even more occupation-specific in the case of licensing compared to occupations that are not regulated. Children whose parents already work in a licensed occupation are more likely to receive these occupation-specific knowledge transfers and so the likelihood of entering a licensed occupation themselves. In addition to knowledge-related transfers, these children may also benefit from their parents’ expertise such as choosing the right exam preparation courses and even get help with the exam preparation. We would also expect the value of the parents sharing their occupation-specific expertise to be higher as the stringency of the licensing requirements increases.

Second, the main justification for imposing legal barriers to enter occupations (in other words, licensing) is the fact that the quality of the product or the service received by the consumer is difficult to evaluate before it has been purchased or consumed. In markets with producers whose quality cannot be observed before purchase or consumption, licensing acts as a mechanism to distinguish between good or good enough quality producers from their counterparts that do not meet the legally mandated quality standards. When the consumer does not have the necessary knowledge to evaluate the quality of the service they are purchasing, then there is the risk that the producer might provide services of substandard quality. The risk and implications of being sold services of poor quality vary depending on the product. For example it is higher in medicine where a person’s life might be threatened, moderately high in the case of legal services and moderately low in the case of a taxi ride. Under such conditions, the reputational and trust effects of family connections can act as a signal to the regulators of the occupation as to the credentials of the applicants. Such effects are likely to be prevalent when entry requirements extend beyond professional exams to include professional experience in the form of apprenticeships and work experience more generally. They are also likely to be stronger in occupations with a higher rate of self-employment and small businesses, with children even able to meet the professional experience by working in their parents’ businesses. We would therefore expect children whose parents work in licensed occupations to have higher chances of following their parents’ occupation.

A look at the data

In the interest of evidence-based policy advice, we can test these assumptions using the Understanding Society Panel Survey (from 2009 to 2022), a large and authoritative longitudinal household panel study in the UK. Details of the statistical approach undertaken can be found in the Appendix.

Our results show that:

- Individuals whose parents work in a routine or semi-routine occupation (sometimes referred to as working-class occupations) are about 33% less likely to work in licensed occupations compared to individuals whose parents work in managerial and professional occupations. We conclude that children from certain socio-economic backgrounds (SEB) face more hurdles in entering licensed occupations. This is likely to be a combination of the high cost associated with becoming licensed and the passing down of occupational expertise and networks.

- Children whose parents work in a licensed occupation are 63% more likely (or they have 1.63 more chances) to also work in a licensed occupation compared to those children whose parents work in an unregulated occupation. We conclude that in the case of licensed occupations there is a higher chance that the parents’ occupation is passed down to their children. We break down these estimates by the type of occupational group in our sample. Here we are interested in whether the impact of licensing on the chance of being employed in the same occupation as our parents is greater in professional and highly skilled licensed occupations (for example, medicine and law). These are occupations that tend to have higher entry barriers in terms of their regulatory requirements and also higher perks in terms of earnings and career progression. In this analysis, we find that the effect of parents’ working in a licensed occupation on the chances of inheriting the parents occupation is stronger in managerial and professional occupations (83% more likely) compared to intermediate and working-class occupations (76% less likely).

- We examine the impact of licensing on the chance of being employed in the same occupation as our parents in occupations where the requirements to become licensed are greater. We find that the chances of inheriting our parent’s occupation are greater for more stringently licensed occupations. In particular, the chances of being in the same occupation as a parent are twice as large for a strictly licensed occupation relative to an unregulated occupation. For less strictly licensed occupations, the chances are 1.4 times higher. We conclude that high hurdles in entering a licensed occupation (and the associated cost) are related to higher chances of the parents passing down their occupation to their children.

How does licensing affect mobility for those from underrepresented backgrounds?

So far we have only looked at how occupational regulation is related to the labour market as a whole. However, the labour market comprises different groups and it is important to consider how licensing might affect individuals who are from underrepresented backgrounds such as women, ethnic minorities and people from lower SEBs. Overall, we would expect the groups to face even greater barriers in entering licensed occupations. Some ongoing research shows that women and migrants, regardless of their SEB, are less likely to be found in licensed occupations. Those who manage to access these occupations find themselves benefiting from the higher wages associated with working in a licensed occupation. However, further research is needed to determine whether licensing specifically affects the labour market prospects of women and ethnic minorities from lower SEBs.

Regulation may also lower the mobility of people, as it might prevent them from changing occupations. This may be because the initial investment required to become licensed is high, such as acquiring qualifications and work experience. This investment may put off people from pursuing opportunities and other occupations.

Reflections on policy

While occupational regulation can deliver some quality assurances to consumers, it is important to reassess its contribution to social mobility policies. Outlined here are the various policy approaches that are relevant to this debate. The underlying philosophy behind the recommendations is that deregulatory exercises do not necessarily adhere to a binary model where an occupation is either regulated or unregulated, as it is commonly implied by proponents and critics of regulation. For example, nobody would want to receive open heart surgery by an unregulated doctor or be represented in court by an untrained lawyer. Instead, what may help is a focus on 2 objectives: (1) the reassessment of the degree of restrictiveness in accessing occupations (rather than the actual incidence of occupational regulation) and (2) the introduction of provisions and policies that promote equity in access to professions for those from privileged and under-privileged backgrounds.

- Relaxation of licensing arrangements: Regulatory arrangements in some occupations are unnecessarily difficult, so there is a case to be made in terms of relaxing the entry barriers to accessing them. Such an approach would mean that the financial costs of becoming licensed or accredited would drop. These costs include the cost of education to become regulated (a direct cost of regulation), but also the indirect costs associated with prolonging the duration of education (for example, in the form of forgone income if the individual was working). The latter might involve the parents supporting the child financially while they are training to become licensed or accredited and so not working, a situation that inevitably benefits children from higher socio-economic groups in terms of affordability. Further, with improving social mobility as a policy target, focusing on occupations where social mobility concerns are more prominent is a more helpful approach in terms of the socio-economic benefits this policy is likely to bring.

- The majority of occupational regulation regimes go back decades. Many are outdated because the occupational circumstances have changed or they might be the product of priorities or plans that are no longer pressing or are better served by other means. In other cases, the barriers to entry have been imposed cumulatively over time on occupations and have added up to what are now significant hurdles to entry and practice. Re-examining the depth and the breadth of licensing arrangements on an occupation-by-occupation basis could be a fruitful way to detect either redundant or excessive constraints that have become institutionalised throughout the history of occupation regulation.

- To illustrate this point, we can draw a recent review of the entry regulations to the engineering profession which revealed ‘double testing for competency’ in the regulatory process. Individuals who had attained the educational qualifications to become licensed were also required to sit a professional exam where they were being tested for many of the same competencies as those tested for during their university education. A final example is the case of ‘double licensing’. This refers to situations where both supervisors and supervisees need to be licensed, even when by law the job has to be performed in the presence of a supervisor so policymakers are advised to scrutinise such cases.

Example: The case of the COVID-19 pandemic.The COVID-19 pandemic crisis exposed some of the inefficiencies of licensing regimes and how these compromise the availability of services. Policymakers could seize this opportunity to re-evaluate the extent to which licensing and how it has evolved over time continues to serve the purposes it was intended to serve. For example, Italian hospitals were overwhelmed by COVID-infected patients and the healthcare system was struggling. As Europe’s hardest-hit country, Italy was forced to relax its regulatory regime by waiving occupational licensing requirements to treat the overwhelming influx of patients. In the UK, entry requirements for healthcare professionals were also temporarily waived to respond to the pandemic crisis, a move that allowed newly qualified practitioners to practise without undergoing further training. During the pandemic, pharmacies became legally allowed to administer COVID-19 vaccinations to the public, an activity previously confined to medical practitioners or pharmacists. In particular, training to administer vaccines by pharmacy technicians was introduced and this training was fast-tracked to one day of instruction. However, in the aftermath registered pharmacy technicians remained unable to administer other vaccines despite being included in the registered healthcare professionals listed in the legislation (in other words, their qualifications to practise as pharmacy technicians being approved by the regulator). In September 2023, the Department of Health and Social Care began a consultation to consider enabling registered pharmacy technicians to supply and administer medicines. The aim of these proposals, if approved, would be to avoid the requirement for patients to see additional healthcare professionals just to receive vaccinations, so facilitating access to medicines and improving patient care. Many US states expanded the scope of practice for nurse practitioners and physician assistants and granted universal recognition of qualifications across different jurisdictions. These examples show that there is scope for the state and its regulators to re-evaluate existing occupational licensing requirements without compromising service quality. |

- Examining the socio-economic composition of those in key leadership positions within regulatory bodies and professional associations is another policy approach. In the occupational regulation literature, we refer to these individuals as ‘gatekeepers’ of the profession. Their task is to set entry standards and screen entrants to the occupation through educational and other requirements. Increasing the representation by those from lower socio-economic backgrounds in these decision-making roles could make such policy decisions more sensitive to such concerns.

Bibliography

Howard Aldrich and Phillip Kim, ‘A life course perspective on occupational inheritance: self-employed parents and their children’, 2007. Published on EMERALD.COM.

Miles Corak and Patrizio Piraino, ‘The intergenerational transmission of employers’, 2011. Published on IZA.ORG.

Becky Francis and Billy Wong, ‘What is preventing social mobility? A review of the evidence’, 2013. Published on RESEARCHGATE.NET.

Maury Gittleman, Mark Klee and Morris Kleiner, ‘Analyzing the labor market outcomes of occupational licensing’, 2015. Published on NBER.ORG.

James Heckman and Stefano Mosso, ‘The economics of human development and social mobility’, 2014. Published on NBER.ORG.

Amy Humphris, Morris Kleiner and Maria Koumenta, ‘How does government regulate occupations in the UK and the US?’, 2010. Published on ACADEMIC.OUP.COM.

Maria Koumenta, Amy Humphris, Morris Kleiner and Maria Pagliero, ‘Occupational regulation in the UK and EU: prevalence and labour market impacts’, 2014. Published on GOV.UK.

Maria Koumenta and Mario Pagliero, ‘Occupational regulation in the European Union: coverage and wage effects’, 2018. Published on ONLINELIBRARY.WILEY.COM.

Maria Koumenta, Mario Pagliero and Davud Rostam-Afschar, ‘Occupational regulation, institutions, and migrants’ labor market outcomes’, 2022. Published on PAPERS.SSRN.COM.

Maria Koumenta, Mario Pagliero and Davud Rostam-Afschar, ‘Occupational licensing and the gender wage gap’, 2020. Published on PAPERS.SSRN.COM.

David Laband and Bernard Lentz, ‘Self-recruitment in the legal profession’, 1992. Published on SEMANTICSCHOLAR.ORG.

Rasmus Landersø and James Heckman, ‘The Scandinavian fantasy: the sources of intergenerational mobility in Denmark and the US’, 2016. Published on NBER.ORG.

Michelle Pellizzari, ‘Do friends and relatives really help in getting a good job?’, 2010. Published on CEP.LSE.AC.UK.

Mark Williams and Maria Koumenta, ‘Occupational closure and job quality: the case of occupational licensing in Britain’, 2019. Published on SCIENCEDIRECT.COM.

Appendix

The data is collected by the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) and covers approximately 40,000 households. The survey allows us to observe the parents’ occupation at age 14 years and match it to that of their children, alongside other demographic and human capital characteristics commonly found in labour force surveys. Our variable of interest is defined as “whether either or both parents’ occupation when they were 14 is the same as the respondent’s at the survey interview date and whether this occupation is licensed”. Information on occupational licensing comes from the UK’s Database of Regulated Occupations (DRO) (Williams and Koumenta, 2020). This is a hand-collected database put together by the author through desk research on the regulatory status of the 353 4-digit occupation unit groups defined by the UK’s ONS Standard Occupational Classification system (SOC 2000). For each occupation, the database contains information such as the type of regulation by which it is covered and the stringency of the regulatory regime (obtained by the following criteria: qualification level (postgraduate, graduate, vocational and so on; years of work experience for entry; other entry requirements such as professional references and whether assessment interviews and tests are required). The DRO is then mapped to the Understanding Society survey. The resulting dataset gives us rich information on individual characteristics, family background and the regulatory arrangements that agree with each occupational code.

The main aim of analysis is to examine whether individuals are more likely to follow their parents occupation when they work in a licensed occupation. We run several logit regressions of the following form:

Yjot=a+b1Rot+b2Xit+eit

Where Yjot is the propensity of child i whose parent (s) is employed in an occupation to at time t to follow the parent(s) occupation. This variable is equal to 1 if the child follows the parent(s) occupation and 0 if not. The main explanatory variable is Rot and measures the presence of licensing in occupation o at time t. The specification includes individual controls (age, gender, ethnicity and education), occupational class and industry controls, all denoted in matrix Xit. We also control for the parents’ and children’s occupational classes to ensure that our results are not picking up general social mobility.